Gallery

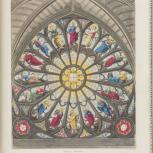

The History of the Abbey Church of St. Peter's Westminster, its Antiquities and Monuments

The History of the Abbey Church of St. Peter's Westminster, its Antiquities and Monuments

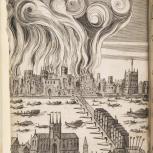

Shilhavtiyah or, The Burning of London in the Year 1666 (Online exclusive)

Shilhavtiyah or, The Burning of London in the Year 1666 (Online exclusive)

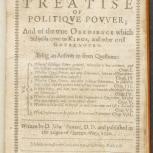

A Short Treatise of Politique Power ... (Online exclusive)

A Short Treatise of Politique Power ... (Online exclusive)

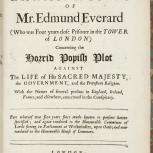

The Depositions and Examinations of Mr. Edmund Everard... (Online exclusive)

The Depositions and Examinations of Mr. Edmund Everard... (Online exclusive)

A Child's History of England (Online exclusive)

A Child's History of England (Online exclusive)

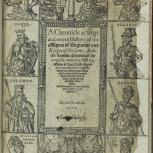

A Chronicle at Large and Meere History of the Affayres of Englande and Kinges...

A Chronicle at Large and Meere History of the Affayres of Englande and Kinges...

An Historical Sketch of the Priory and Royal Hospital of St. Bartholomew

An Historical Sketch of the Priory and Royal Hospital of St. Bartholomew

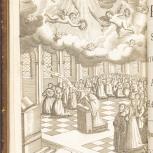

Domus Carthusiana

Domus Carthusiana

Einige Predigten von Heinrich Otto Schrader, Hofprediger zu St. James's...

Einige Predigten von Heinrich Otto Schrader, Hofprediger zu St. James's...

Catalogus librorum manuscriptorum bibliothecae Cottoniae

Catalogus librorum manuscriptorum bibliothecae Cottoniae

Leaf containing part of scholastic commentary on Psalm 101:2-5

Leaf containing part of scholastic commentary on Psalm 101:2-5

Prayers and Thankesgiving to be Used by all the Kings Maiesties Loving Subiects...

Prayers and Thankesgiving to be Used by all the Kings Maiesties Loving Subiects...

A Treatise of Melancholie

A Treatise of Melancholie

It is hard to overestimate the climate of uncertainty—and deep anxiety—that permeated English society during the sixteenth century. The fundamental relationship between God and man was debated and rewritten by theologians on the continent in the decades following 1517. People wrestled with the concept that there was more than one possible route to achieving salvation, and that learned clergy disagreed which one was right. Making the correct choice would determine the fate of their eternal soul and was their responsibility, rather than mediated by priests and the church. Whereas everyone previously shared the same faith, individuals now faced choices whether to identify as Catholics or Protestants. Levels of state-sponsored persecution grew as England’s official religion switched from one to the other according to the personal beliefs of the monarch. Individuals choosing to follow their consciences felt trapped between obedience to God and to their ruler. As a result, what had started out as theological debate at times flared into an increasingly violent struggle on the streets, often accompanied by iconoclastic destruction of religious images in buildings and churches. The deep religious divisions of the sixteenth century cast a long shadow over politics throughout the seventeenth century.

In London the impact was particularly unsettling. Its strong trading links with many of the places from where Protestant dissent was emerging meant a rapid influx of new ideas. This was linked to an increasing number of refugees seeking a place of safety where they could worship in peace. As France descended into chaos during the Wars of Religion, thousands of Huguenot refugees crossed the Channel seeking shelter in the city. They brought with them new trades and skills such as silk weaving, watch-making, silver-smithing and increasingly sophisticated financial services. Immigration was therefore a contributory factor behind London’s rapid population growth during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

Friends, family and neighbours were joined by strangers spreading new ideas, and those adhering to the ‘old’ religion soon began to feel like outsiders in their own city. The environs of London were often the site for militia musters, a reminder that overseas invasion was a threat, but equally, that the troops could be mobilised against the civilian population if the need arose. Indeed, the use of London as the main place of execution for the leaders of the Pilgrimage of Grace—a huge rebellion against religious change in 1536—served as a further warning to the city’s inhabitants.

The rising population had an impact on society in other ways, particularly the need for greater provision for the sick and the poor. Yet the crisis was exacerbated by the Crown’s land-grab during the dissolution of the monasteries, since they had traditionally served this purpose, especially in more rural areas. Over half of all London property was monastic, and much of it was sold into private hands and converted to diverse secular uses. The Charterhouse, for example, first became a private mansion and, later, the original site of Charterhouse school. The former Dominican priory of Blackfriars became the location for a theatre, and Henry VIII converted the leper hospital of St James into St James’s Palace.

Yet some monastic buildings were partially saved from privatisation and reformed as hospitals, such as St Thomas’s and St Bartholomew’s, both of which are still with us today. Others became places of worship for new congregations. For example, the church for ‘Germans and other strangers’ was established in 1550 on the site of the former Austin Friars monastery. It was soon catering for an estimated 5,000 residents from the Low Countries, by the 1570s London’s largest migrant group.