Gallery

Bassus of the Whole Psalmes in Foure Partes

Bassus of the Whole Psalmes in Foure Partes

The Vision of Pierce Plowman (Online exclusive)

The Vision of Pierce Plowman (Online exclusive)

The Pilgrim's Progress (Online exclusive)

The Pilgrim's Progress (Online exclusive)

Christie’s Old Organ, or, 'Home, Sweet Home' (Online exclusive)

Christie’s Old Organ, or, 'Home, Sweet Home' (Online exclusive)

The Noble And Joyous Book Entytled Le Morte Darthur

The Noble And Joyous Book Entytled Le Morte Darthur

Leaf from The Golden Legend

Leaf from The Golden Legend

The Holy Bible, Conteyning the Old Testament and the New...

The Holy Bible, Conteyning the Old Testament and the New...

The Booke of the Common Praier and Administracion of the Sacramentes...

The Booke of the Common Praier and Administracion of the Sacramentes...

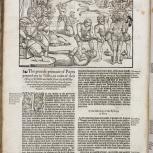

Actes and Monuments of Matters Most Speciall and Memorable...

Actes and Monuments of Matters Most Speciall and Memorable...

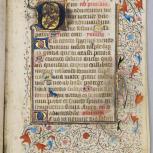

Book of Hours (Sarum use)

Book of Hours (Sarum use)

Twelfth Night

Twelfth Night

Bildnisse: 24 farbige Handzeichnungen

Bildnisse: 24 farbige Handzeichnungen

Prior to the Reformation, culture was inextricably bound up with church doctrine and practice, especially in the expression of religious ideas in daily life through literature, music and art, centred on the parish church with its vividly decorated walls, painted religious images and liturgy accompanied with music. Doctrinal reform therefore had a dramatic impact on all these aspects of culture, as new traditions replaced old. Iconoclasm stripped out images, whitewashed paintings and destroyed relics in churches. New forms of secular expression, often influenced by imported Humanist ideas from the Italian Renaissance, took their place.

One of the pivotal changes brought about by the Reformation related to language. Previously all church services and texts were conducted and written in Latin, something now increasingly limited to Catholics. In contrast, the Protestants insisted that the language of communication with God should be a language that everyone could understand, not just the priests and educated laity. Thanks to the rise of new communications technology, highly influential religious texts such as the Book of Common Prayer in 1549 and a succession of translations of the Bible, culminating in the King James Version of 1611, were printed in English and circulated in vast numbers. This, in turn, had an enormous impact on the development of the English language.

From the 1530s, playwrights and players contributed to the formation of a culture in England that was more inspired by secular influences. New ideas spawned by the Reformation were incorporated into their work, in contrast to passion plays and performances designed to reinforce the Christian message. Authors and playwrights such as Edmund Spenser, Nicholas Udall, John Bale, and, ultimately Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, and William Shakespeare brought tragedy, history, comedy, satire, and drama to thousands of people through published prose and verse, as well as directly through performances in the burgeoning theatre scene around London. Some of the new secular cultural forms that the Reformation inspired were met with strong criticism from more radical Protestant groups, often called Puritans.

Music and art underwent a similar transformation, although the latter was adversely affected by the iconoclasm that destroyed older forms of religious art. The Tudor court in London provided patronage for predominantly continental painters like Hans Holbein, under whose influence indigenous painters, such as Nicholas Hilliard, began to flourish. The English Renaissance therefore took a markedly different course from that in Italy, where emphasis was placed on the rediscovery of the ancient classics and a consideration of secular allegorical imagery. However, it was at this time, both in Italy and England, that the role of the patron became more important and influential, especially ‘art for art’s sake’ rather than religious patronage designed to save one’s soul.

In music the Reformation also found a creative outlet. During Henry VIII’s lifetime, singing in church and during religious practice began to shift from Latin to the vernacular. This came at a time when composers began to write in a more chordal style that enabled words and speech to be more clearly identified by listeners. The trend was accentuated by a massive increase in psalm-singing singing in English in the latter decades of the sixteenth century. This undoubtedly paved the way for change within secular music as well, since composers now had a wider audience and new patterns with which to play.