London: E. Whitchurch, 1541

[E.M.W.] 341a (fol.)

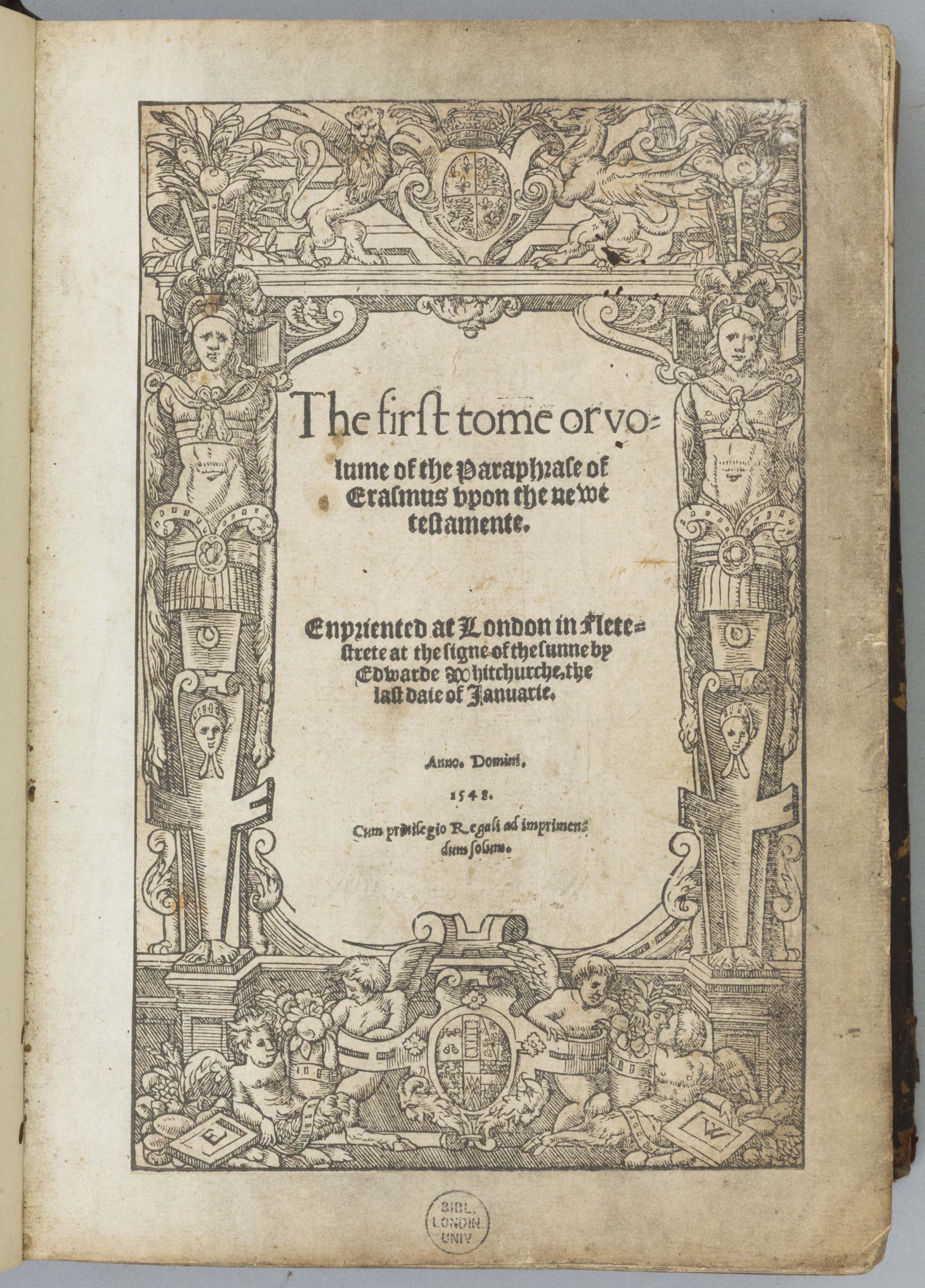

Praising ‘the multiplication of good books by the printer’s pen’ to further Christ’s church, John Foxe wrote in his introduction to The Whole Workes of W. Tyndall, Iohn Frith, and Doct. Barnes (shown) that worthy books from former ages were not preserved because the art of printing had not yet been invented. The Dutch-born, Swiss-based humanist Desiderius Erasmus (1467-1536) was perhaps the first scholar to rely entirely upon the printed word to spread his message. Erasmus helped to pave the way for the Reformation by insisting upon returning to the Bible’s original text and translating the New Testament afresh from Greek into Latin. He also criticised such aspects of contemporary Christendom as the cult of the saints: for example in Moriae Encomium (Praise of Folly), which he finished at Thomas More’s house on one of several visits to England. Initially Erasmus’s choice to write in Latin limited his influence, although he later fuelled a translation industry in England. His Paraphrases upon the New Testament, written in Latin and promptly translated into English by the future Mary Tudor among others on the initiative of Queen Katherine Parr, were extremely influential. In 1547 Edward VI ordered them to be made accessible in every parish in England.